By World Family Education

For families living internationally, short-lived stressors such as moving or changing schools are a familiar challenge. But when temporary difficulties turn into long-term hardships, families have to contend with a much greater level of stress.

Open-ended crises that continue to build over a longer period of time can include:

Each situation will be different, and each family will deal with it differently. It’s important to understand, recognize, and address some of the ways an ongoing crisis impacts your family’s mental, emotional, and spiritual health.

Recognize the Crisis

Families navigating any traumatic situation must first recognize they are in a crisis. A typical crisis involves a traumatic event followed by a recovery period. However, in an ongoing crisis, the trauma is often rolled out over an extended time. It may build with time, getting worse and worse until it ends or subsides slowly, and parts of the recovery process can be intermingled with the cycles of trauma.

In this situation, the mental, emotional, and spiritual toll on family members can be hidden and remain unresolved. The effects of trauma may be overlooked because the whole family experiences it. Stress has become the new normal, and recognizing it as a response to trauma may be difficult. Parents can become preoccupied with their own day-to-day survival and emotional responses, while failing to notice the stress in their children. To effectively help their family, parents must accept the existence of trauma, recognize its impact, and act to address it.

Responding to Crisis

The crisis response model from the National Organization for Victim Assistance (NOVA) describes the emotional, physical, behavioral responses to trauma. From this, we learn that when people experience trauma, they often respond with shock and disbelief. This is true whether or not there is a dramatic beginning of the experience. People experiencing trauma have difficulty admitting it’s happening, and may go to great lengths to ignore or minimize it. Once the shock fades, people often shift into a mixed emotional response including anxiety, fear, anger, frustration, guilt, and shame.

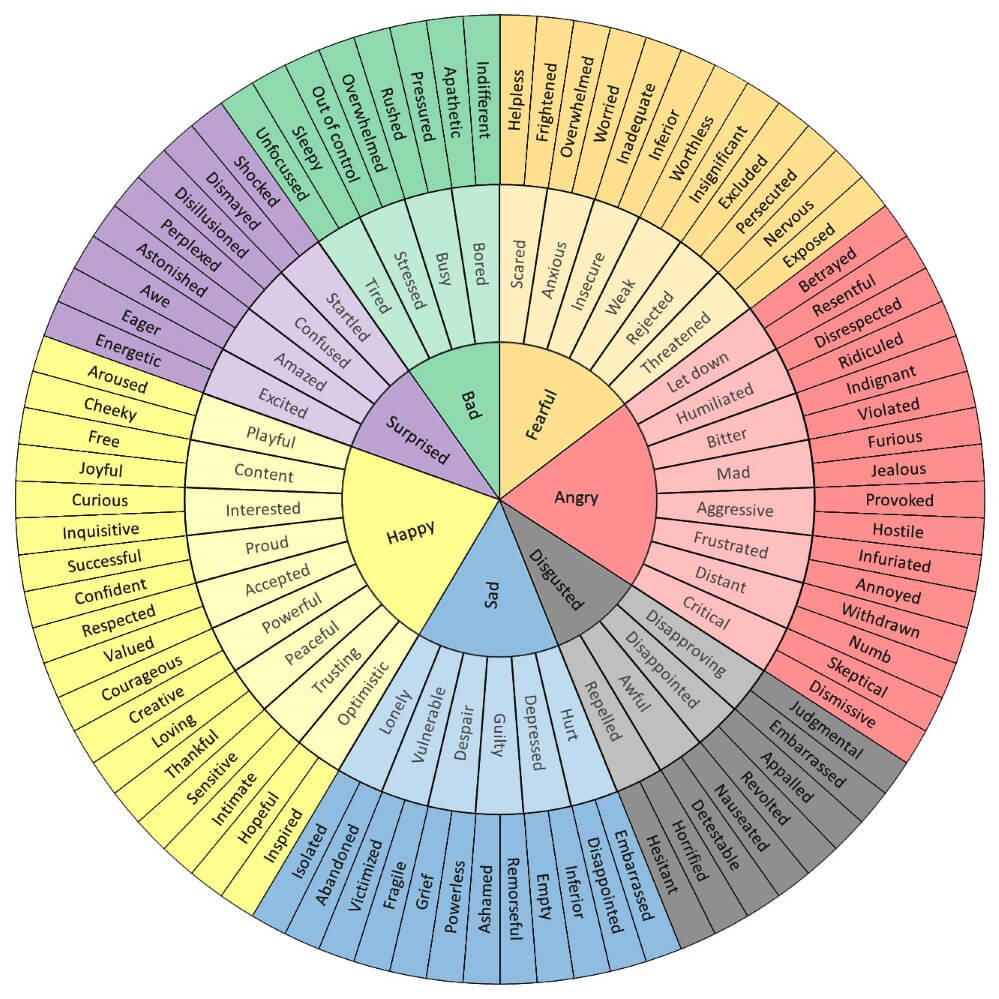

These responses may happen in sequence, but in a prolonged traumatic experience, the crisis isn’t a one-time experience and may build over time. This means the emotional response pattern can be repeated over and over again, resulting in a tangled mix of emotions at any given time.

It’s important for parents to recognize their own emotional response as well as what their children may be feeling. Donna Jackson Nakazawa, author of Childhood Disrupted, points out that chronic unpredictable stress has a long lasting effect on a child’s brain. This impact is even more profound when the parent’s actions and responses are unpredictable. The best thing a child can have in these situations is a strong relationship with supportive and loving parents.

Also, children often mirror their parents’ emotions. Because of this, parents should be aware of words and emotions they express in front of their children, and ensure they model a healthy response to the ongoing crisis. It’s a great idea to learn more about coping styles used by each member of your family. Read more about coping styles in Ute Limacher’s description of How to Deal with Different Coping Styles.

The Impact of Loss

An extended crisis will always include the experience of loss. Some of the losses will be obvious. A family may lose tangible possessions such as home, school, friends, etc. But some of the loss will be much more intangible. Intangible losses would include the loss of freedom of movement, significant events (graduation, weddings, etc.), a sense of security and safety, control, or even sensory input (being in the sun, physical contact with friends, seeing people in person, etc.).

In a drawn out and open-ended crisis, both tangible and intangible losses can be without closure or ending, making the normal grieving process difficult. The challenge is to allow the grieving process to begin while accepting the possibility that resolution may never occur. Without this, a person may find it very difficult to move on with life in a healthy way.

Helping your child identify their losses will empower them to articulate their emotions. Parents can do this by asking them about people, places, and things that they miss. It’s helpful to allow children to talk about their losses without trying to fix or minimize what they share. Parents can model a healthy response by describing their own losses along with their hopes for the future.

Grief

With loss comes grief. Each person expresses grief in their own way, but most will experience the common components of avoidance, frustration, anger, feeling overwhelmed, and moving on (See Kübler-Ross’ Five Stages of Grief). These emotions don’t necessarily happen in order and tend to come like waves. Over an extended grieving process, they will be quite jumbled up and hard to distinguish.

It is very important to help your family deal with grief. Experts on the dynamics of families living internationally, such as Ruth Van Reken, point out that unresolved grief is a major challenge for cross-cultural kids. For some, it can cause significant emotional problems throughout their lives.

To help resolve grief,

If you sense that your child’s grief goes beyond a normal response, is presenting as depression, or results in destructive or self-harming behavior, please seek professional counseling help immediately. There are therapists who specialize in working with international families and can do so online. You can find some of those at World Family Education’s Family Counseling and Coaching page. It would also be advisable to seek professional counseling or coaching for your family if your prolonged crisis lasts more than a few months.

Bouncing Back

A key to surviving and thriving in an ongoing crisis is the ability to bounce back, and be even stronger after a trauma. Ideally, parents should begin to help their children build resilience before a trauma. But this capacity can be nurtured during a crisis as well.

Encourage the growth of resilience in your family with these tips, adapted from sources such as Karen Young at Hey Sigmund (.com) and Dr. Suzanne M. Anderson at Restorative Community Concepts (.com). Remember to work toward your own growth in these areas and model it for your kids.

Recognize What is Important

For many families, the demands and distractions of normal life often take over and mask or replace values that are truly important to a family. Times of crisis tend to uncover those values and present an opportunity to take stock of your family’s priorities. When the crisis is over and you return to “normal” life, you can redefine your family’s values, recalibrate your goals, and rebuild your lives around them. Keep the good things you have discovered as you move into and beyond the recovery and resettling period.

Perhaps you’ve learned that your family really enjoys playing board games together. Before the crisis, you may not have made time for that. After the crisis, you have the opportunity to recalibrate around that value and make room for a game night. Maybe you discovered that your kids really enjoy reading a book together, making dinner together, or exercising together. These do not have to be lost. Some strategies you adopted to deal with the emotions of the crisis might be helpful to continue after the crisis, and even beyond the recovery phase.

Affirm Identity

A child’s sense of identity is quite different from an adult’s. There is far less history and insight into the future in a child’s understanding of who they are. Their self perception connects to their very immediate abilities, experiences, and relationships. This means that a prolonged crisis can have a big impact on a child’s sense of identity.

Make sure to help your child see the bigger picture of who they are, and their significance and importance to the world. Cultivate a sense of identity that is rooted in the family identity. Talk about your family’s values and how they are reflected in each member.

When it is all said and done, this experience will be a significant part of who your family is, but won’t define it. Be intentional about nurturing your family relationships, because a loving, united, and communicating family can weather any storm.

If your ongoing crisis involves a transition to home educating, read World Education’s page Temporary Home Education for International Families.